Cash

Not all money is treated in the same way. There is an obvious difference between having some hard currency in your pocket versus having the same amount deposited in a bank; the former is easier to access (and spend) when compared to the latter1. Building up on this simple intuition, a generalisation of this notion can be made, and is given the name of cash. Wikipedia defines it like so (emphasis ours):

Definition 2.10: In economics, cash […] is money in the physical form of currency, such as banknotes and coins. In bookkeeping and finance, cash is current assets comprising currency or currency equivalents that can be accessed immediately or near-immediately […].

The idea of "varying degrees of immediacy" with regards to access jumps out of this definition, as does the word assets. This term has a very important meaning, if somewhat difficult to pin down in a precise manner. As always, we must start with Wikipedia's attempt at a definition (emphasis ours):

Definition 2.11: In financial accounting, an asset is any resource owned by the business. Anything tangible or intangible that can be owned or controlled to produce value and that is held by a company to produce positive economic value is an asset. Simply stated, assets represent value of ownership that can be converted into cash (although cash itself is also considered an asset).

Definition 2.11 nicely rounds up the circle; there is the idea that "an entity" (a business) can own "things" (assets), and that these things have a monetary value (though how exactly that is determined is not our concern just yet). There is also some kind of "conversion function" which enables us to go from "things" into the most basic representation of value — in this case cash — and vice-versa.

We have already mentioned bank money and deposits. They are of course assets, but they belong to a special group of assets — a group so special, in fact, that it is arguably the raison d'être for the discipline of Computational Finance. These are called financial assets, and are defined as follows (emphasis ours):

Definition 2.12: A financial asset is a non-physical asset whose value is derived from a contractual claim, such as bank deposits, bonds, and stocks. Financial assets are usually more liquid than other tangible assets, such as commodities or real estate, and may be traded on financial markets.

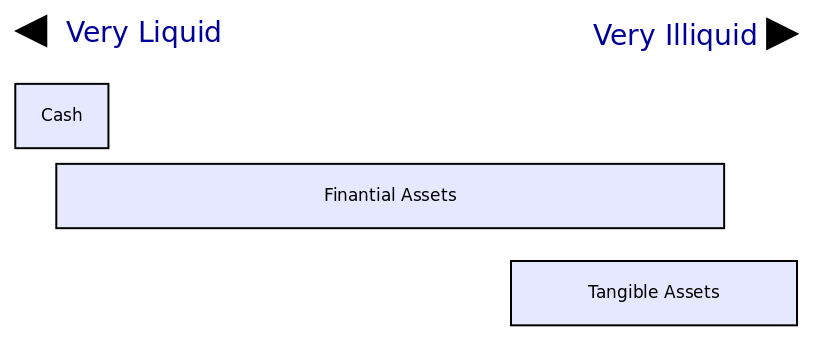

Many points worthy of discussion emanate from this seemingly trivial definition — such as derived — but we must leave them for a more suitable setting, or else risk entering into too rocky a terrain. For now we shall narrow our focus to the term liquidity. Liquidity is the idea that the process of conversion of an asset to cash may have a certain amount of "friction" associated with it; that it may not always be as smooth as one would wish. Having value stored in a financial asset implies transitioning value into a more illiquid state (i.e. further away from cash), and converting value back to cash means having value in a more liquid state (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Conceptual model of the liquidity of assets.

The same figure also illustrates the point that some financial assets are more liquid than others — that is, more easily convertible back into cash. Note that cash itself is composed of currency or currency equivalents (Definition 2.8), which is to say financial assets that are very liquid such as bank deposits form part of the accounting definition of cash. Liquidity, in this sense, is a spectrum of possibilities, and to make matters more complicated, it is also a dynamic process: as time marches forwards, a financial asset may (or may not) change its characteristics with regards to liquidity. For example, a bank under stress may restrict access to its depositors, making deposits less liquid.

Somewhat confusingly, the idea of liquidity also applies to entities themselves. Wikipedia tells us that (emphasis ours): "[in] accounting, liquidity (or accounting liquidity) is a measure of the ability of a debtor to pay their debts as and when they fall due." These notions are related because, by definition, an entity in liquidity trouble does not have access to a "sufficiently large" pool of liquid assets. It is also normally clear what is meant by the word depending on context, so we need not trouble ourselves with it any further.

At any rate, thus far we have introduced the concepts of cash and liquidity; the final pillar of this triad is the notion of cashflow, which finally starts to bring the system into motion. It is defined as follows (emphasis ours):

Definition 2.13: A cash flow is a real or virtual movement of money […]. [A] cash flow in its narrow sense is a payment (in a currency), especially from one central bank account to another; the term 'cash flow' is mostly used to describe payments that are expected to happen in the future, are thus uncertain and therefore need to be forecast with cash flows […]. [It] is however popular to use cash flow in a less specified sense describing (symbolic) payments into or out of a business, project, or financial product.

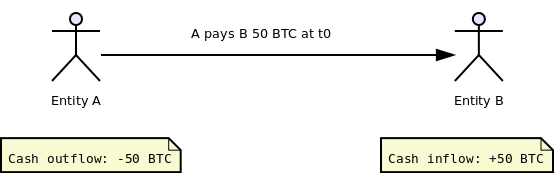

A cash flow is a vector quantity, where the magnitude is an amount in a given

currency, and the direction indicates whether cash is flowing out of an entity

or into it. The cash flow sign convention stipulates that negative values

represent cash outflows and positive values represent cash inflows, with

regards to an entity that acts as the reference point. Figure 2 depicts

the relative nature of the direction by means of a payment of 50 BTC from

Entity A to Entity B. From A's perspective, there is an outflow of -50

BTC, whereas B sees an inflow of +50 BTC.

Figure 2: Cash inflows and outflows, relative to an entity.

The magnitude of a cash flow (50 BTC in the example above) is known as the

notional or principal, and is defined as follows (emphasis ours):

Definition 2.14: The notional amount (or notional principal amount or notional value) on a financial instrument is the nominal or face amount that is used to calculate payments made on that instrument. This amount generally does not change and is thus referred to as notional.

It is useful to think of Cash flows as events, and thus they are commonly referred to as cash flow events and modeled as observations or the expectation of an observation. The temporal aspects are given by an associated time point, which details when the flow occurred — if in the past — or is due to occur — if in the future. In the example above, the flow occurred at time \(t_0\). It is customary to use the letter \(t\) to refer to a time point, with \(t_0\) being typically used to represent an initial or origin time point and subsequent time points being designated as \(t_0, t_1, t_2, \ldots, t_n\).

In the example above we dealt with an individual cash flow, but it is an atypical example manufactured solely to introduce the concept. More often than not, they will appear in groups — often quite large ones. Where there are several related cash flows, is often useful to bundle them together and refer to them in the aggregate. A group of related cash flows is known as a cash flow stream. In typical usage, the expression cash flow stream often implies the cash flows are in the future, though it may not always be used with this meaning. In this text, we take it to mean "a group of related cash flows" regardless of temporalitiy2.

Cash flows are one of the most fundamental particles from which financial assets can be constructed; and, ultimately, all financial assets can be decomposed back into a stream of cash flows. This property has some very interesting consequences, as we shall see much later on, since it makes possible the replication of the behaviour of a given financial asset by assembling, very carefully, groups of other kinds of financial assets in a such a way as to match precisely the cash flow streams of the original asset. We are getting ahead of ourselves, though, and much domain exploration is needed before this topic can be broached. For now, we shall head back to our excursion over the foundations for one final round of core concepts.

| Previous: Currency | Next: Trading | Top: Domain |

Footnotes:

In these days of contactless payments, you may beg to differ. Bear in mind, however, that you still need the payment infrastructure in order for contactless to work, whereas you do not for hard currency. In a scenario where the payment networks run into issues, hard currency would suddenly be at a premium.

Depending on the context, a group of cash flows may also be known as a leg. We shall delay the discussion of this term.